Don't Catch the WAV

a.k.a. Looking at alternatives to the ubiquitous audio file format.

I get sent a lot of music. As a longtime music journalist, that’s not anything unusual, but it does mean that a lot of promos land in my inbox—the vast majority of them unsolicited.

Digging through those emails is part of the job, and over the years, I’ve seen just about everything, from personalized, essay-length promo spiels to typo-riddled blurbs that barely qualify as sentences. And when it comes to actually sharing the music itself, the platform options are seemingly endless. Spotify. SoundCloud. Dropbox. Google Drive. WeTransfer. FATdrop. DISCO. PromoJukeBox. Haulix. That’s just a partial list of the various sites and services people use, and it doesn’t even include the folks who still send audio files as email attachments. (Pro tip: don’t do that.)

There’s no one “right” way to send music to journalists (or anyone else in the industry), but some methods are definitely more advisable than others. Back in June of 2020, I actually did my best to outline some of those methods here in the newsletter—that particular edition was literally titled “How to Talk to Journalists (and Get Them to Check Out Your Music)”—and while I’m admittedly revisiting some of the same ground here, today I wanted to narrow the focus a bit further.

That’s because there’s one file-sharing practice that’s still incredibly common, despite the fact that it routinely causes headaches for those receiving the music:

People are still sending WAV files, and they probably ought to stop.

I’m not the first person to make this plea. London artist Scratcha DVA—who I interviewed last year (albeit about a different topic)—has been waging a very public battle against the WAV format for years, mostly via his (highly entertaining) Twitter account.

But why? It’s just a file format. Who cares? For Scratcha—and many other DJs—the problem is largely one of space, in the sense that WAVs simply take up too much of it. Of course, that’s by design. WAV is a lossless format, which means that unlike MP3 files, the audio remains uncompressed. However, it also means that WAV files are much bigger than MP3s—up to 10 times larger, in fact—and if you’re a digital DJ with a limited amount of room on your laptop’s hard drive or the USB sticks you use for gigs, that can be a problem. And it’s not just DJs who are affected—think about recordings of classical music performances, or long-form experimental works. Any time that something extends beyond the length of the average pop song, if the audio is rendered as a WAV file, it’s going to gobble up a whole lot of memory.

That being said, as hard drives (and USB sticks) continue to become bigger—and cheaper—over time, these kinds of space-related complaints will likely subside. Unfortunately though, there’s another big problem with WAV files, and it’s one that’s largely gone ignored in the public square: metadata. (For the uninitiated, metadata is essentially “data about data,” and when it comes to music, it refers to all of the information stored within an audio file about the artist name, song title, album title, etc.) Unlike MP3s (and several other formats as well), WAV files are terrible with metadata, and that can cause all sorts of hassles, especially for anyone who receives a large volume of music. (And for anyone thinking “who cares?,” know that metadata problems cost musicians and songwriters potentially billions of dollars each year.)

Oddly enough, the problem isn’t that WAV files can’t hold metadata; if you drop a track into iTunes (which is now just called Music), you can still manually input all of the relevant information, and it will pop up whenever you subsequently open the program. The problem is that if you then try to share that WAV file with someone else, all of that information might very well disappear. Last year, I penned an article on metadata issues in the music industry—it was part of a feature series that I put together for Byta, another file-sharing platform—and it included this quote from Sam John, a cutting and mastering engineer who runs Precise Mastering in the UK:

If I encode metadata into WAVs, it can get lost very easily. Any conversion at any stage just loses it. I can do it, but the next step down the road, it’s gone. It’s kind of a waste of time.

He wasn’t exaggerating. For a myriad of technical reasons that I won’t get into here, WAV files tend to lose their metadata when they’re copied, often retaining little more than whatever file name they were given. Speaking from my own experience, that means I regularly receive ZIP files of tracks that can’t be easily identified; when I attempt to preview them (on a Mac, by pressing the spacebar), I get a window like this:

Not very informative, is it? And it doesn’t help that many artists, labels and PR reps will frequently title the folders they send over as just “WAV,” forcing recipients—especially the ones with a crowded Downloads folder—to play detective if they want to figure out who actually made the tunes.

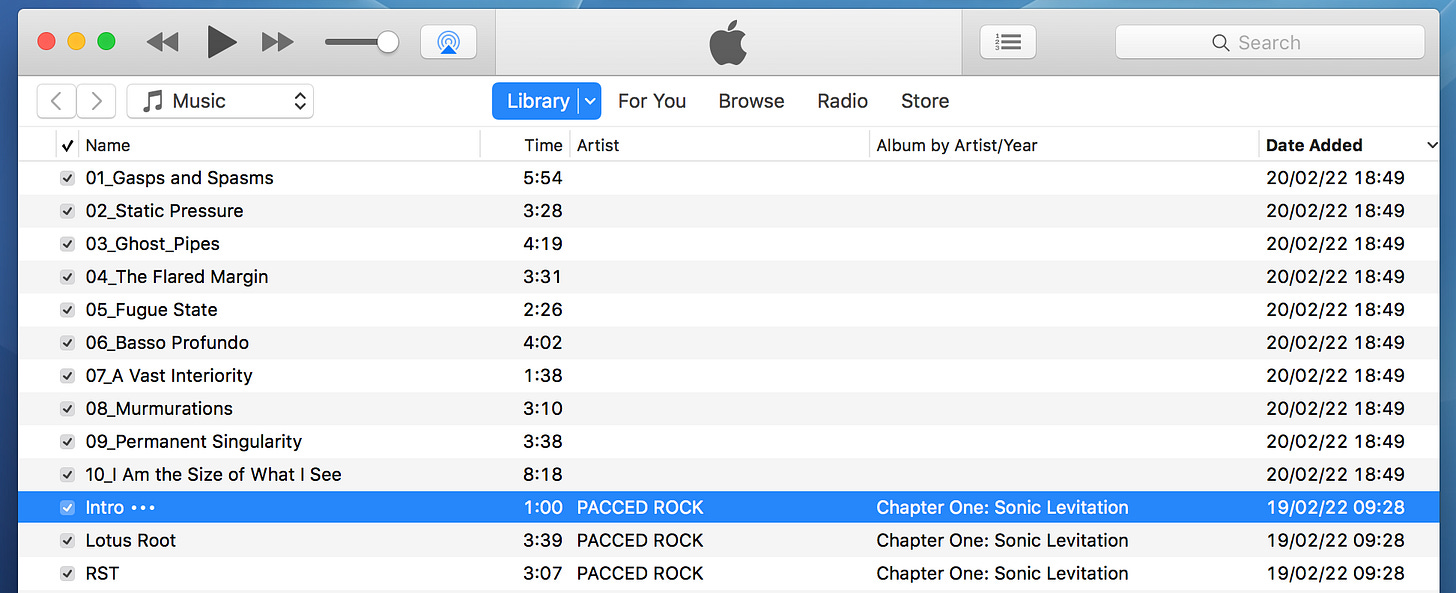

Those same recipients won’t find any help from iTunes either. Here’s what it often looks like when I drop an album of WAV files that I’ve been sent into my library:

Who made these songs? What is the album called? Based on this, I have no idea, and if the folder they were sent over in doesn’t offer more information, then the only way to find out is to search for individual song titles (preferably the ones with less common words) in my inbox, or even worse, start plugging them into Google.

Can some of this be mitigated by better file-naming practices? Yes. As a general rule, labeling a folder—or even a sub-folder—with only the word “WAV” is probably a bad idea. Similarly, individual WAV files can be labeled with the artist name and song title. (Some people will also include information like the album title, catalog number and label name, amongst other things, although doing so often results in some rather unwieldy file names.) Even then, you’re running the risk of annoying any recipients who like to keep a tidy digital library. (In the streaming era, that’s admittedly a shrinking cohort.) For example, here’s what happened when I dropped the promo files for an upcoming EP from In Fields into iTunes:

At least the artist name is in there, but what’s the name of the EP? Are these tracks in the right order? Investigating further is the only way to find out, and even if all the information is eventually confirmed, properly organizing the files in iTunes requires going in and doing a bunch of data entry.

Before someone cries “first world problems” or chalks this whole piece up to a journalist complaining about the free music that they’ve been sent, it’s important to remember that this is a problem of scale. Manually inputting the proper metadata for a release or two is clearly no big deal, but when people working in music—artists, DJs, journalists, booking agents, promoters, playlist and radio programmers, music supervisors, etc.—are receiving dozens (or even hundreds) of songs and releases every day (i.e. much more than they could possibly listen to), choices have to be made. There’s a numbers game at work, and if something isn’t properly labeled, whoever’s listening to it—if they even bother to listen in the first place—is going to have to be pretty damn enthralled with the music to go back and track down the identifying information. WAV files obviously aren’t the sole cause of missing / incomplete metadata—it’s incredible how many artists and labels simply neglect to add it in the first place—but they absolutely contribute to this problem.

But what about audio quality? Isn’t that important? Remember, WAVs are lossless. They’re supposed to sound better, and that’s why people send them. Although some people claim that they can’t hear the difference between WAV files and MP3s, there’s no denying that the former, simply by being uncompressed, are of a higher quality. (If you want to give a mastering or cutting engineer a heart attack, suggest pressing a vinyl release from a track in MP3 format.)

And it’s not just file senders perpetuating the use of WAVs; recipients often demand it. Many commercial / large-scale radio stations don’t consider MP3s to be “broadcast quality,” and while things aren’t quite as strict in the world of electronic music, when artists are playing digital files on massive sound systems, questions of audio quality are massively important. Despite the existence of people like Scratcha DVA, many DJs out there refuse to play anything but WAV files, as they’re far more concerned with fidelity and bassweight than potential metadata mishaps.

Thankfully though, this doesn’t have to be a binary, either / or choice between WAVs and MP3s. WAV is not the only lossless format out there, and its most common alternative (AIFF) offers the same level of audio quality while doing a much better job retaining metadata. (Another lossless option, FLAC, is often preferred by audiophiles, and while it’s also good with metadata, its compatibility issues—for instance, it doesn’t work in iTunes—mean that it’s probably not ideal for promotional purposes.)

Habit plays a huge role in why people use certain formats (and certain platforms, for that matter), but while WAVs might be the current industry standard for high-quality audio, AIFF files can tick that box without putting all of the relevant metadata at risk. (When AIFFs have been properly named and all of the metadata has been input correctly, problems like the iTunes snafus highlighted above largely cease to exist.) Sending out AIFFs may elicit a few confused responses—even within music circles, the format is still unfamiliar to many people—but once recipients understand the benefits, they’ll likely appreciate the switch from WAV files.

Better yet, why not make everyone happy and send multiple file formats? Everyone in the music realm has different needs and preferences, so why not send audio in a way that offers maximum flexibility? Options are a good thing, and there’s no rule against sending over links to MP3s, WAVs and AIFFs in the same promo email. (Another pro tip: make those links separate, so that recipients—especially the ones who only want MP3s—don’t have to download a massive ZIP file.) In that same spirit, why not throw in a streaming link too? Remember, not everyone wants a download, and even if they do, there’s still a decent chance they’ll want to give something a quick listen before parking it on their hard drive.

When it comes to sending music files, artists and labels tend to focus on one question: how do they sound? That’s obviously important to file recipients as well, but many of them—especially the busy ones—have two other concerns that shouldn’t be overlooked: ease of use and utility. WAV files fall short in both categories, and as the sheer volume of music that someone receives increases, those drawbacks increase exponentially. The format will probably always have its loyalists, and that’s fine, but given that WAVs aren’t the only option for high-quality audio on the block, perhaps their hegemony is no longer warranted.

Shawn Reynaldo is a freelance writer, editor, presenter and project manager. Find him on LinkedIn and Twitter, or drop him an email to get in touch about projects, collaborations or potential work opportunities.