Big Beat Was Worse Than You Remember

A partial accounting of how a genre that conquered the globe in the '90s has aged so badly.

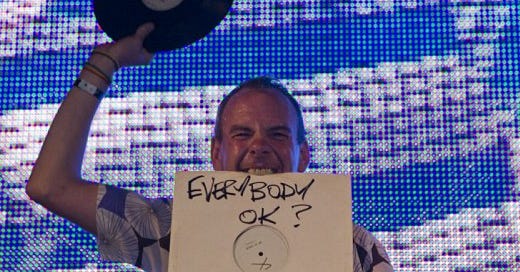

I’ve got the ’90s on my mind. Granted, the ’90s are the one decade that pretty much never disappears from electronic music, but after listening to the latest episode of the No Tags podcast, I’ve plunged myself into a very specific ’90s rabbit hole, one soundtracked by Fatboy Slim, The Chemical Brothers, The Crystal Method and a slew of big beat also-rans.

My intentions were good. The No Tags crew, with the help of guest commentator (and Manchester house / garage mainstay) Finn, devoted their most recent broadcast to something they’re calling Big Beat Cinema, “outlining the core canon and basic tropes … [of] the ultra-stylish heist movies of the late ’90s and early ’00s – think Ocean’s Eleven, Mark Wahlberg’s The Italian Job, Snatch and even The Matrix.” While film was the main focus of the episode, their conversation also touched upon the sheer absurdity that characterized much of that era’s pop culture, and pointed out the outsized role that big beat played in soundtracking the movies they were putting under the microscope.

This late-’90s / early-2000s time period is something I’ve previously tackled here in the newsletter. Back in 2022, I dove deep into Paul Oakenfold’s impressively bad 2002 album Bunkka, and just a couple months ago, I revisited nu-skool breaks, which might be the only Y2K-era dance music genre that’s never experienced any kind of significant revival. Big beat, however, is something that I’ve only mentioned here and there over the years, which is strange, because it was the sound that first introduced me to electronic music in the first place.

I was in high school when the “electronica” trend was foisted upon the American public as the proverbial “next big thing,” and when artists like The Prodigy, Daft Punk and Fatboy Slim suddenly started popping up on the local alternative rock radio stations—thanks to the grunge explosion a few years earlier, the San Francisco Bay Area had two of them during much of the ’90s—I quickly took an interest in this “new” sound from across the pond. (The fact that everything I was hearing could be traced back to the house, techno, electro and disco sounds that had originated years earlier in the Black and brown communities of my very own country was something I would figure out much later, but back in 1996, that history wasn’t part of the narrative being spun by the commercial music industry.)

Listening to the No Tags episode took me right back to that time, triggering memories of all sorts of artists and songs, many of which I hadn’t listened to in decades. Though I knew that big beat on the whole hadn’t aged well—that’s the one observation you’ll hear again and again whenever the genre comes up in conversation—I dove into my archives, sure that I would come across some long-forgotten gems. That was my original plan for today’s edition of First Floor: to compile and share a list of big beat tunes that had defied the odds and stood the test of time.

There was just one problem. Big beat really has aged terribly, and the more I dug, the more stinkers I found. Nostalgia had clearly clouded my memory over the past 30 years, because even the artists and songs that I remembered liking in my younger days have in most cases not really held up. Exasperated, I eventually decided to alter course, which is why today’s newsletter is not a celebration of big beat, but a look at where and how it went wrong. The songs below—which, admittedly, are just a sampling of the big beat canon—aren’t necessarily terrible, but they are very much “of their time,” and as it turns out, that time is in many cases not worth revisiting—at least not as a listener.