A Music Industry That Doesn't Sell Music

a.k.a. It's a lot easier to capitalize on people's dreams of being an artist than it is to actually market whatever music they make.

In the latter half of the 2000s, physical music sales fell off a cliff, and while the blow was temporarily offset by a rise in digital sales (e.g. MP3s and, oddly, ringtones), it took less than a decade for that market to collapse as well. For all the ongoing talk in recent years about a vinyl revival, a CD revival and even a cassette revival, these things are all niche concerns in an industry where streaming now generates more than 80% of recorded music revenue in the US. Even as a company like Spotify receives wave after wave of bad press, and is openly reviled within certain music circles, its streaming platform is literally more popular than ever, with a subscriber base that continues to experience “record growth.”

Streaming is cheap, easy and popular with consumers, and that goes a long way towards keeping the whole enterprise afloat, particularly in a financialized economy driven by investment capital. Spotify might have suffered a net loss of €532 million in 2023, but barring some major meltdown that sends it users fleeing in droves, its investors are unlikely to abandon ship either. The proposed Living Wage for Musicians Act, introduced earlier this month by Congressional representatives Rashida Tlaib and Jamaal Bowman, could potentially shake things up, at least in the US, but it’s not yet close to becoming law. And based on the initial response—I’m paraphrasing, but there’s a whole lot of “the government shouldn’t be regulating consumer prices” and “artists should just work harder if they want to make a living” sentiment out there—the bill has an extremely tough road ahead.

Artists, however, continue to speak out. When things have reached a point where even a seemingly successful musician like James Blake is now publicly complaining about the current state of affairs, it should be obvious that the industry is trending in a worrisome direction. The idea of selling music to make a living has already become borderline laughable, and with streaming income being not only minuscule, but disproportionately distributed to a small cohort of rights holders at the tippy-top of the revenue pyramid, there don’t seem to be many viable economic pathways for anyone who’s not a global pop star, a legacy touring act or a shareholder at a major label.

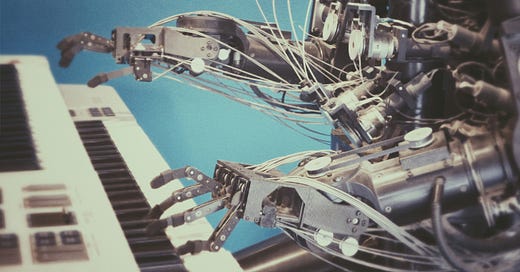

Things are bad, and with the widespread adoption of AI technology right around the corner, the situation is in danger of getting much, much worse.

Over the weekend, Rolling Stone published a feature about Suno, an AI startup that’s working to develop what the publication describes as a “ChatGPT for music.” The company’s model is already capable of producing works that sound uncannily human, and its technology continues to improve at what seems like an exponential rate. The article’s author, Brian Hiatt, describes a song created by the model—the ominously titled “Soul of the Machine,” which resulted from a text prompt of “solo acoustic Mississippi Delta blues about a sad AI”—as “the most powerful and unsettling AI creation I’ve encountered in any medium.”

That alone will likely disturb the growing ranks of AI pessimists out there, but the piece also features a separate passage that’s not only more concerning, but explicitly indicative of how the tech industry perceives art:

Suno appears to be cracking the code to AI music, and its founders’ ambitions are nearly limitless — they imagine a world of wildly democratized music making. The most vocal of the co-founders, Mikey Shulman, a boyishly charming, backpack-toting 37-year-old with a Harvard Ph.D. in physics, envisions a billion people worldwide paying 10 bucks a month to create songs with Suno. The fact that music listeners so vastly outnumber music-makers at the moment is “so lopsided,” he argues, seeing Suno as poised to fix that perceived imbalance.

Setting aside Silicon Valley’s ongoing abuse of the word “democratization,” the takeaway here is very clear: Suno would like to flood the market with not just music, but with artists—one billion of them, in fact. In this guy’s mind, today’s working musicians are effectively gatekeeping the creative experience, and he’d like to level what he sees as a “lopsided” playing field. (The rather plausible possibility that Suno’s technology was developed using the copyrighted work of those working musicians—the company’s founders “decline to reveal details of just what data they’re shoveling into their own model”—is just a bit of depressingly ironic icing on the cake.)

Is this cavalier attitude toward existing artists and their work shared by many within the burgeoning AI sector? Probably, but this kind of perspective isn’t unique to AI. I’d argue that it’s an outgrowth of two seemingly opposing ideas, both of which have been gaining strength for quite some time.